THE HOLY CENTER

A SWEDENBORG FOUNDATION PUBLICATION

First Swedenborg Foundation Printing

Copyright 1983 All Rights Reserved

The

Swedenborg Foundation 139 East 23rd Street New York, N.Y. 10010

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 83-060258

ISBN 0-87785-172-7

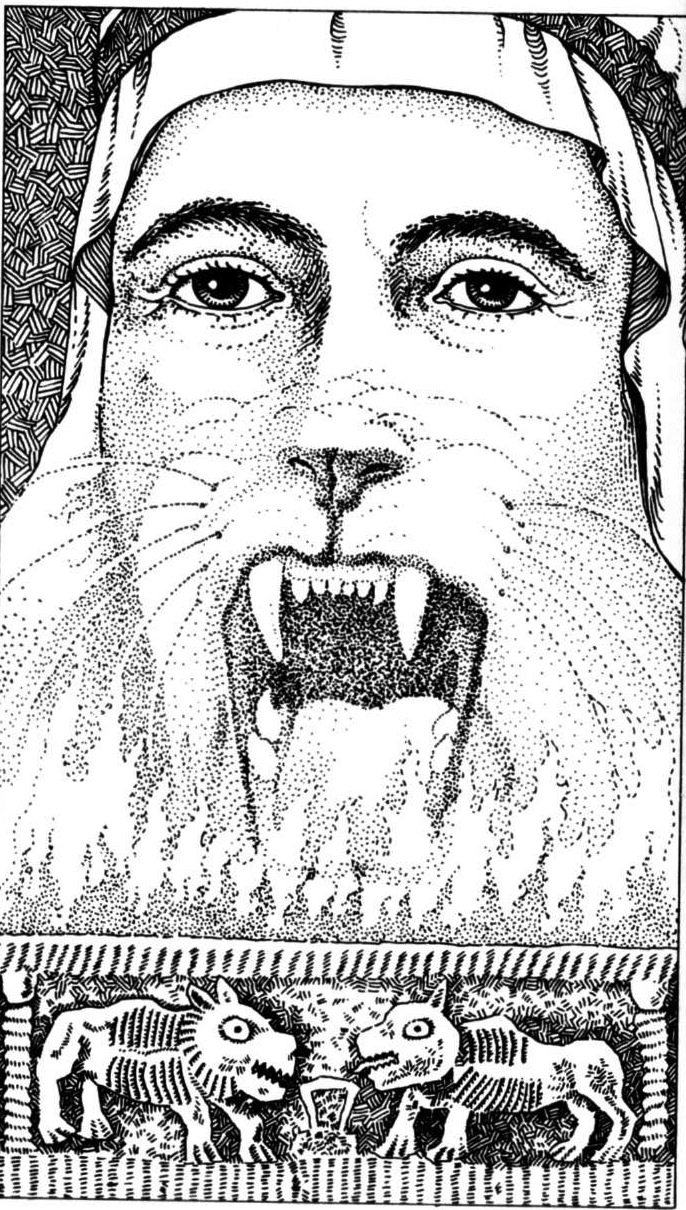

Cover Design and Illustrations by Nancy Crompton Manufactured in the United

States of America

About the Author

Dr. Dorothea Harvey effectively combines her study and teaching of religion with the practical and personal power of religious symbolism, healing and mystical experience. Her ministry is one of concern for spiritual and personal growth. Many people have helped to create the material presented in this book by sharing their reactions and daily experiences, and have applied what they've learned about the power of the Old Testament to daily living.

Dr. Harvey has done extensive archeological study in the Near East and has a solid understanding of biblical stories and customs. Her knowledge of Hebrew and other Semitic languages complement well her interest in the Old Testament as it relates to her own life, as well as allowing her to speak with authority of its content and power.

Other publications by Dr. Harvey include works on the literary forms, the prophets, the forms of worship, and the women of the Old Testament.

Dr. Harvey is a 1943 graduate of Wellesley College. She earned her M. Div. at Union Theological Seminary and her doctorate in Literature of Religion at Columbia University. She has taught at Wellesley College, Milwaukee-Downer College and Lawrence University, and has been a professor of religion at Urbana College since 1968 and its chaplain since 1975. She is the minister of the Swedenborgian Church in Urbana, Ohio.

Dr. Dorothea Harvey

Introduction

The tabernacle was for Israel the sign of God's intent to dwell with her, the place of God's continuing Presence in her midst. The story of the tabernacle and of the worship and the sacrifices associated with it, might seem to be the ancient history of some remote tribe, except for one thing: The story consists largely of directions for the people's use of the tabernacle, that is, their approach to the Presence, their worship, and their living in its light. And when we study the directions, we find ourselves in the Presence, hearing God's Word to us about our approach to the Lord, our doubts and confusions as we try to bring our lives toward God's light to worship.

I began my study of this part of the Bible with hesitation. But what I found was a direct and sensitive response to my inner need as the words of the Bible became God's Word to me. And I learned that I was not alone in my confusions. Others, from ancient Israel on, had suffered them before me, and had found their way to God's continuing and supporting Presence notwithstanding. My first assumption in this writing is, then, that God's Word is present in the Bible, and speaks to us in the most practical ways of the issues of our inner lives. If we need help in our approach to finding God, these chapters of the Bible are for us.

My second assumption is that the images in the Bible are words of power. "The LORD is my shepherd" needs no defence or explanation. The image itself speaks, with new power each time we hear it, if we let ourselves respond to it at all. The images relating to God in the end of the Book of Isaiah have an equal immediate power. God is the Ruler coming with strength who

. . . will feed his flock like a shepherd, he will gather the lambs in his arms, he will carry them in his bosom,

and gently lead those that are with young.

(40:10-11)

God relates to Israel as a mother who cannot

forget her sucking child,

that she should have no compassion on the son of

her womb.

(49:15)

God is the hero of the creation warfare who pierced the chaos dragon of the universe to make a cosmos (51:9). God, the Maker of Israel, is the husband who will have compassion on his briefly forsaken wife (54:5). God is warrior putting on righteousness as a breastplate (59:17), glory rising as light upon his people (60:2). God will rejoice over Israel "as the bridegroom rejoices over the bride" (62:5). God is "our Father," "our potter" for us the clay (64:.1). And "as one whom his mother comforts," so Israel will be comforted by God like a child held in her lap (66:12-13). This end of the Book of Isaiah proclaims once and for all the one God of all history and all creation, but the language is not our labored writing of sentences about God's omnipotence and omniscience. The language of the Bible is that of concrete, vivid images to which we must respond, with feeling and living as well as thought, in order to know their meaning and their power.

Every reader of the Bible has recognized this power of image in the psalms and in the prophets. What I have found in these chapters describing the worship associated with the tabernacle, is the same power of image. This, I believe, is the language of the Bible as a whole, its history and religious practices, as well as its poetry and prophecy. Israel had a political life in this world, and her history as recorded in the Bible, may be studied and checked for literal accuracy in the light of the history and culture of other ancient peoples. But the history of Israel recorded in the Bible is also, I believe, the history of the inner life and growth of every human being. My intention in this work is to look at the biblical directions for the tabernacle and the worship associated with it, as true history to be studied with all the help of the critical understanding of its original cultural setting that I can find, and at the same time as true image to which I must respond to hear God's Word to me.

This approach is not new. It is based on an earlier study of the tabernacle, The Jewish Sacrifices, by the Rev. John Worcester, a Swedenborgian minister who based his work on the findings of the 18th century scientist and theologian Emanuel Swedenborg. Worcester's work, published in Boston in 1902, was part of a significant influence of Swedenborg in the thinking of the time. William James was doing his pioneer work in psychology and religion. Elwood Worcester and others were active in the Emanuel Movement to bring the insights of religion, psychology, and medicine together to enhance the lives of people. Swedenborgians, with their commitment to the Bible as God's Word, their equally strong sense of the power of symbol, and their acceptance of science as a natural ally of religion, were well suited to such endeavors. In 1909 the visit of Freud and Jung to this country eclipsed these Swedenborgian efforts, but, of course, contributed enormously to popular awareness of spiritual-psychological reality and to serious, continued interest in the relationship of religion, psychology, and spiritual growth.

The present work is the result of my engagement in John Worcester's original study of the tabernacle and its sacrifices, to make it available in new and modern form. It is offered with appreciation of Worcester's and Swedenborg's insights, and with thanks to the Swedenborg Foundation for suggesting the project.

1. The Offering for the Tabernacle

The LORD said to Moses, "Speak to the people of

Israel, that they take for me an offering; from every man whose heart makes

him willing you shall receive the offering for me. And this is the offering

which you shall receive from them: gold, silver, and bronze, blue and purple

and scarlet stuff and fine twined linen, goats' hair, tanned rams' skins,

goatskins, acacia wood, oil for the lamps, spices for the anointing oil and

for the fragrant incense, onyx stones, and stones for setting, for the ephod

and for the breastpiece. And let them make me a sanctuary, that I may dwell

in their midst. According to all that I show you concerning the pattern of

the tabernacle, and of all its furniture, so you shall make it."

Exodus 25:1-9

The LORD said to Moses, "Speak to the people of

Israel, that they take for me an offering; from every man whose heart makes

him willing you shall receive the offering for me. And this is the offering

which you shall receive from them: gold, silver, and bronze, blue and purple

and scarlet stuff and fine twined linen, goats' hair, tanned rams' skins,

goatskins, acacia wood, oil for the lamps, spices for the anointing oil and

for the fragrant incense, onyx stones, and stones for setting, for the ephod

and for the breastpiece. And let them make me a sanctuary, that I may dwell

in their midst. According to all that I show you concerning the pattern of

the tabernacle, and of all its furniture, so you shall make it."

Exodus 25:1-9

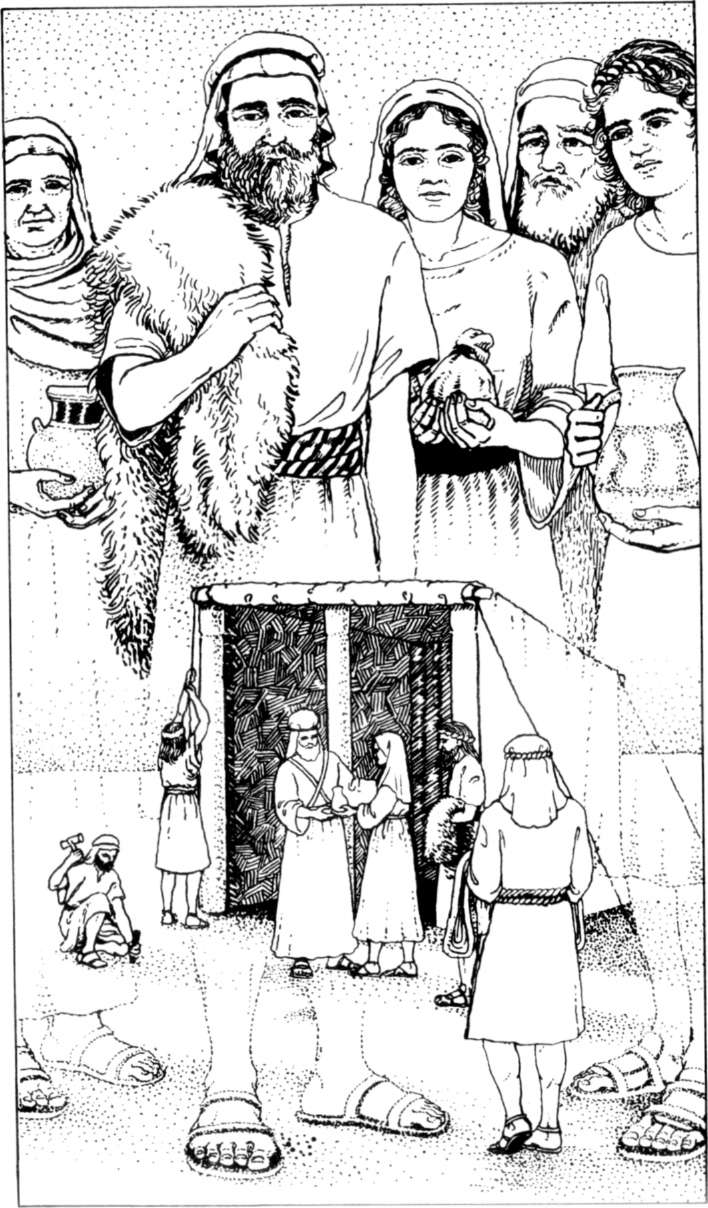

When the people of Israel were in search of their identity and sense of purpose in the world, they looked to their origins, to the deliverance from Egypt, the making of covenant, the encounter with the Presence of God in its symbols of fire and cloud on Sinai. They looked to those momentous events in history through which they became conscious of themselves as a people in relationship to God. And according to the tradition, the last in this series of momentous original events was God's commandment to build a tabernacle, a place where the Presence of God might "dwell in their midst."

Words of origin are words of power. They speak to our identity as much as to ancient Israel's. As the Passover wording tells us, every Jew "in every generation" is responsible to know the deliverance from Egypt as a contemporary event, to know that he or she has shared in that deliverance as a son or daughter of the covenant. Christians who take these words of spiritual origin seriously know too that these events of deliverance, covenant, and Presence are living and contemporary.

Let us look at the details of this account to see its significance both in the light of the ancient tradition of Israel, and in the light of our willingness to let the images speak to us with power. The first point in the account is simply the command of the Lord that an offering be taken. Moses was to ask for offerings from the people of Israel to make a sanctuary in which their Lord might dwell. If this is indeed God's living word, it commands us also and with power. That Presence is also with us as vividly as with our fathers and our mothers in every element of the Biblical account as we hear the Lord's word commanding us to prepare our awareness of that holy center, the tabernacle, that place of dwelling of our Lord with us.

It is the tabernacle we are concerned with here, and not the temple. Israel's tradition includes at least two symbols for the place of God's dwelling on earth. The temple in the holy city, Jerusalem, is the eternal, ever- present dwelling on the mountain to which we journey, singing our songs of pilgrimage as we approach its gates from east or west or north or south. In the Book of Revelation, the city New Jerusalem is itself the dwelling place of God. The numbers of this city suggest its permanence, its spatial dimensions; it is a city built foursquare, and with twelve gates facing equally the four corners of the earth.

The tabernacle has a different connotation. It is the tent in which God sojourns, the statement of God present with us in our time, in our journeying through deserts and migrations and changes of state. Its numbers are process numbers: threes, or fives, numbers that seem to encourage the mind to move on and continue the series. Its touch with the Divine is an awareness of our identity in God's eyes, where we are in our history. Nathan said to David when he had in mind the building of the temple,

'Thus says the LORD: Would you build me a house to

dwell in? I have not dwelt in a house since the day I brought up the people

of Israel from Egypt to this day, but I have been moving about in a tent for

my dwelling. In all places where I have moved with all the people of Israel,

did I speak a word . . . saying "Why have you not built me a house of

cedar?" '

2 Samuel

7:5-7.

The temple is here distinguished from the tent in which God moves with the people.

After the temple was destroyed and the people were in exile, both connotations, the return to that one place on earth, and the trust in God's dwelling with the people anywhere, took on special significance. In the Book of Revelation in the New Testament the temple is the image for the new heaven and new earth. In the gospels John uses the tabernacle word for dwelling in a tent when he says of the incarnation: "the Word became flesh and dwelt among us" (John 1:14). The Jewish tradition keeps this tabernacling meaning in its word for the Presence: the Shekinah, or literally, the dwelling in a tent.

The tabernacle is here, of course, not just one literal tent filled with the Lord's life. It is hard to conceive of God's taking satisfaction in dwelling in a tent or in a house or in any inanimate, unconscious form. The tabernacle is, however, a powerful symbol of God's dwelling among people. For the Christian its deepest meaning is the Divine Humanity itself, Jesus' life on earth, as John's wording indicates. In a more general sense it speaks of the receiving of the Divine by the human soul, making conscious, living minds in which God can delight and dwell. In this sense every human being is called to be a church or holy place, that is, a tabernacle of God, a means for the Divine influence to come into the world.

If we are each called to be a church or holy place, what do we need to do then, to bring it to reality? Material for the temple came from afar, from Lebanon, or even from "God out of Heaven" in Revelation 25:10. The materials for the building of the tabernacle in Exodus, however, came from the people themselves: good things of quite definite kinds which the Lord had given them. These they brought together according to the Divine pattern to receive the Lord's blessing. Every one of the materials Israel was to bring was already within them ready for them to offer to the Lord's ordering to find its meaning. A tabernacle, or a church, in which the Lord delights is not an unorganized throng of people, nor of feelings and thoughts within one person. Nor is it a band organized in a selfish way for selfish purposes. It is people who bring together their affections, experiences, knowledge, and powers, to be used, to receive and bring forth the Lord's life for good and for blessing. Constrained offerings of merely external, formal profession of religion contribute nothing here either. They are not receptive of the Lord's spirit of blessing. The offerings are genuine offerings, elements lifted up by "every one whose heart makes him willing" from love for the Lord and for the neighbor, and the order they receive from the Lord is their own genuine order, set free to function in harmony.

All the wealth of that list of materials is already there, in our inner person. The list itself is a catalog of wonder: gold, silver, and bronze, blue and purple and scarlet stuff and fine twined linen, goats' hair, tanned rams' skins, goatskins, acacia wood, oil and spices, onyx stones, and stones for setting. Each image has its power. First come the precious metals: gold and silver and bronze. The rocks of the earth symbolize permanent, basic truths, such as that life is from God and not our own creation, or that all men die. Metals are mined from rock, but can be molded into many shapes. They are basic truths which depend for their shape upon circumstances, and are called laws. The gold needed for the tabernacle is awareness of the law of life from God, that is, of good, or love itself. The silver is awareness of the laws of usefulness to the neighbor, that is, of truth or wisdom, the form love takes in action. And the bronze, the copper made tough with tin, is the functional, natural good of a life of love and truth in the external world. The tabernacle is not built on arbitrary guesswork. It rests first on knowledge of these functional laws. The first step has to do with love, then, as the base for truth, as our living it makes love complete in action.

Blue and purple and scarlet stuff come next. The Lord as the center of love and light is the reality our sun symbolizes. The varied reception of this Divine love and light is spiritual color; the absence of it is darkness. Blue is like the dark of night lighted up with white, the color of wisdom and of heaven, of the lighting up of intelligence in the darkness of the mind. Blue-purple, the color mentioned here, is the kindling of intelligence from love to the Lord, or the heavenly love of truth. Scarlet is red lighted up with white or yellow. It represents the fire, or good of love, or the Lord's love brought out from its presence in the inner person into a more distinctly understood love for the influence of the Lord in human beings. The Hebrew speaks here of "double" scarlet, or mutual love, vividly apprehended. Purple is red and blue together. This purple, of the ancient dyes, was a red-purple, representing the warmth of love for the Lord, or the heavenly love of good. This beauty of color, the delight of the kindling of intelligence concerning things of God, is an essential element in this dwelling place of God with us. It is the law of love received with joy as we begin to be conscious of God's will to be at home in us.

The colors are followed by the white of fine twined linen. Its associations are with truth of celestial origin and with the clean "righteousness of saints" in which their lives are clothed (Rev. 19:8). Readiness to be cleansed and to be clean is part of preparation for God's dwelling. The colors of the cloth and the pure whiteness of the linen are set off by the black of goats' hair, that typical stuff of the Beduin black tents, signaling people on the move, or camped briefly for a season. The black wool is the practical external good of mutual helpfulness in learning from the Lord, or in this case, of tent protection for the traveler on the way of life.

The "tanning" of the rams' skins is literally in Hebrew "reddening," and recalls the red leather tent in which ancient Near Eastern desert tribes carried their sacred objects with them as they journeyed. A bas relief of such a small tent set on the back of a camel is carved in stone at the entrance of the ancient temple of Bel at Palmyra in the Syrian desert, and still shows traces of red paint on the stone. Together with these coverings of skins, the tough, fine-grained acacia wood for the frame is a realistically practical element, a strength of functional knowledge of the Lord as sustainer and protector in the immediate, down to earth stages of living. The sense of sacred reality within is important, but the wooden frame, the tough minded courage to see and to deal with practical daily issues without letting go of the sacred, is an equally essential strength for any actual tent or move.

Light for our seeing in the tabernacle is from olive oil in the lamp, that is the light of the genuine, unselfish goodness of the Lord's own mercy and healing power, not the light of selfish pride or enmity. And to bring the pure goodness with which the Lord blesses the dwelling place to distinct and pleasant consciousness, there are the perceptions of spices for the anointing oil, and prayers and songs of penitence and praise going up as spiritual incense. Finally there are the onyx and other precious stones for the ephod and breastpiece. These are specific and clearly defined doctrines concerning the Lord's kingdom, shining with the changing light of every varying shade of truth and love as new vision brings new insight.

This is a long list of specific meanings. It seems somehow too good to be true. Were nomads of that early time aware of all of this when they used their sacred tent? Doesn't the list read more like a kind of late and arbitrary game imposed by Worcester or Swedenborg? Is this just another scheme designed to give a sense of power to those who know the answers?

I think not. All ancient peoples seem to have had a sense of powers in the world around them. A living tree, the earth, a rock, a mountain, a flame of fire, each had its own distinctive power not to be taken lightly. I think of a recent sunset. Its power for me was not the series of colors and shapes. The same colors reproduced on film, or by a play of lights on fountains, are striking, but they do not break in on me with another dimension and make me listen. Ancient peoples knew meaning breaking in. They would not have used Swedenborg's 18th century western words to convey the meanings. We might not either. But his words are witness to the reality of that other side of experience. He brings to the conscious, verbal side of me a wealth of emotional reality. And I regain, in my inner world, at least a little of the wonder of real meaning in the nature of things, of which I had been deprived.

The implication of God's command to make the offering for the tabernacle, is that all these materials, all the essentials for the building of that holy center where God would dwell within the human heart, were already there in the possession of the people. They needed only to be brought to light, by being willingly offered to the Lord, to come to conscious power and meaning in a coherent whole. It is as if the typical black tent of some ordinary human journey were found to be furnished with treasure within, to be a habitation fit for the adventure of encounter with the Lord and King. It is like receiving a glorious, unexpected present.

If we let this section of Exodus speak to us as Word of God, we become aware of a wealth of varied gifts and experiences already within our inner person, ready to be brought to light. We have looked at the material in this catalog of wonder: the gold, silver, and bronze, the blue and purple and scarlet stuff and fine white linen, the black goats' hair, red-tanned rams' skins, goatskins, acacia wood, oil and spices, onyx stones, and stones for setting. We have begun to speak of the symbolism of these materials. They have to do with love as the reason for truth, with awareness that love and truth must be actually received and lived in order to be understood.

They have to do with the stirring of beauty and excitement when the mind is lighted up with new insight, with the joy of cleanness, the fear and joy together of being ready for a move, the wonder of lighting a light, the pleasure of sudden awareness that smells good or shines like a gem, the flare of color in a desert place.

We have begun to speak of these symbolisms. And yet we know intuitively that there is no single, final meaning in any of these images. It is frightening in a sense to realize there is no one interpretation or authority to fall back on, to tell me the final meaning they should have for me or what my inner life is like. And yet, it is partly because of this that they are such powerful symbols of the realities of the inner life. They are not fixed. They are the essential materials for the sanctuary in which the Lord would dwell with me in my life journey. I must take the responsibility for letting them speak to me, to know the power of what my bronze or blue or pure white linen means for me. But if I hear these words, I can no longer avoid the knowledge that these things are there within. I sense their power to help me know the Presence of the living God, the kingdom of God "in the midst" of me.

What, then, does all this have to do with me in my life here and now?

I think for me, it is the gift of knowing who I am. It is the potential of looking to my origins and knowing the presence of my Creator dwelling with me. These offerings are not strange to me. I have a sense of the power of love and truth, of the color and fragrance and light added to life by new awareness, of the need and joy of cleansing, of the fact that I do move and grow, and of ways leading to unknown parts just now beginning to open before me in the journey of my growing. The promise of this account in Exodus is not that these are suddenly handed to me. We all have moments of insight like this. As isolated moments they often seem to give a momentary life, and then be gone. The promise here is that these aspects of my being belong together, giving a spiritual harmony to my experience. In these my Maker wills to dwell with me and be my strength, my Lord. I have a wealth within. I am alive not only to the outer world around me, but to the deeper levels of my life. I am prepared to go on the adventure of my life, to find the God who made me, and become myself.

![]()

Sit quietly a moment, and prayerfully. Recall the beginnings of the people of Israel, God's call to Moses, the exodus from Egypt, the covenant with God at Sinai that created a people conscious of its relationship with the Lord of history. Feel their sense of God's presence and God's power in history. Now keep this quiet and prayerful openness of mind, and ask God's blessing and protection on the openness, and recall the beginnings of your spiritual history, the moments that spoke to you of your relationship with the meaning of your history. Feel your sense of God's presence and God's power that have brought you to this moment.

And now read again the Lord's Word to Moses in Ex. 25:1-9, and hear it as spoken for you by the God who created you.

The LORD said to Moses, "Speak to the people of Israel, that they take for me an offering; from every man whose heart makes him willing you shall receive the offering for me. And this is the offering which you shall receive from them: gold, silver, and bronze, blue and purple and scarlet stuff and fine twined linen, goats' hair, tanned rams' skins, goatskins, acacia wood, oil for the lamps, spices for the anointing oil and for the fragrant incense, onyx stones, and stones for setting, for the ephod and for the breastpiece. And let them make me a sanctuary, that I may dwell in their midst. According to all that I show you concerning the pattern of the tabernacle, and of all its furniture, so you shall make it."

Lord, thank you that you made me and gave me life and love. Thank you that you will to dwell with me. Help me with my fear of finding so much within. There is so much I hardly know, and yet somehow I know that I am on a journey in my life, though its beginning and its ending are both beyond me. Help me with my fear of things too big for me. But thank you for that sense of meaning and of journey. I could not live without them. Thank you for the gift of hunger for your presence in my life. Thank you that I can trust myself to you and know that you go with me. Thank you, Lord. Amen.

2. The Ark of the Testimony

They shall make an ark of acacia wood; two cubits and a half shall be its length, a cubit and a half its breadth, and a cubit and a half its height. And you shall overlay it with pure gold, within and without shall you overlay it, and you shall make upon it a molding of gold round about. And you shall cast four rings of gold for it and put them on its four feet, two rings on the one side of it, and two rings on the other side of it. You shall make poles of acacia wood, and overlay them with gold. And you shall put the poles into the rings on the sides of the ark, to carry the ark by them. The poles shall remain in the rings of the ark; they shall not be taken from it. And you shall put into the ark the testimony which I shall give you. Then you shall make a mercy seat of pure gold; two cubits and a half shall be its length, and a cubit and a half its breadth, and you shall make two cherubim of gold; of hammered work shall you make them, on the two ends of the mercy seat. Make one cherub on the one end, and one cherub on the other end; of one piece with the mercy seat shall you make the cherubim on its two ends. The cherubim shall spread out their wings above, overshadowing the mercy seat with their wings, their faces one to another; toward the mercy seat shall the faces of the cherubim be. And you shall put the mercy seat on the top of the ark; and in the ark you shall put the testimony that I shall give you. There I will meet with you, and from above the mercy seat, from between the two cherubim that are upon the ark of the testimony, I will speak with you of all that I will give you in commandment for the people of Israel.

Exodus 25:10-22.

The inmost thing in Israel's tabernacle was the ark, the point of actual meeting with God's Word. And the inmost of a live church, or mind, is the part which hears the Word of God as commandment, applied to life, as the living thought of God. And so, as the first section of Exodus 25 on the tabernacle described the materials needed that the Lord might "dwell in their midst," this second section on the ark concludes, "There I will meet with you, and ... I will speak with you of all that I will give you in commandment for the people of Israel."

The tabernacle is a "tent of meeting," where we meet the Living God. "I will meet with you, to speak there to you. There I will meet with the people of Israel, and it shall be sanctified by my glory; I will consecrate the tent of meeting" (Ex 29:42-43). The effective center of the meeting here described, was the ark with its testimony within, that is, the Word or Truth of God in its power.

This is the tent of meeting, the meeting of the Divine transcendent Other and the human mind. For some this meeting means an experience of ecstacy, a heavenly escape from the bounds of the finite and of this world. For Israel it meant the mystery of the divine Word that called them to live the life of God's pure Will in the world, accepting the limits of the human mind and will. The image for that transcendent Otherness is the pair of cherubim. The image for the Presence of God's Word here in this world is the chest of wood, the ark, with God's commandments within. And the image for the mystery that brings these two together, is the gold, or love.

The first to be mentioned is the ark, the specific symbol of God's Presence. In later times the ark dwelled invisible behind the veil of the holy of holies. But early records show the ark going ahead of the people on the march "to seek out a resting place for them" (Num. 10:33). It was when the priests bearing the ark entered the Jordan that the waters parted for the people to pass through (Josh 3:15). It was the ark that devastated the Philistines (I Sam. 5). And it was when Uzzah, unauthorized and unprepared, put his hand on the ark that he died, and David feared to bring it into Jerusalem (II Sam. 6). In Israel's tradition, the power within it was God's presence in the ten commandments, the most important testimony to God's Word.

It is when we hear the Lord's commandments in order to do them that the power of the Lord to save and bless becomes real. John's statement of this is the same truth that was represented by the manifest Divine Presence in the ark of the testimony: "He who has my commandments and keeps them, he it is who loves me . . . and I will love him and manifest myself to him" (John 14:21). The ark commands the attention not of the natural level of a person, which could almost be identified, so to speak, as a sort of immortal animal, but of the inmost, spiritual level which knows the Lord and draws support and guidance consciously or unconsciously from God.

The ark, like the frame of the tabernacle, was of acacia wood. This desert hardwood was not a fruit tree, valued for the food it gave, but valued for its own sake. It is the type of mind which is strong in resolve, from the knowledge that the Lord has conquered evil. The dimensions of the ark, related to the numbers five and three, symbolize this knowledge of the Divine protection in all the length and breadth and depth of human life.

The next element mentioned is the gold, the essence of goodness, or love itself, the connection between the human and the Divine. The wood was to be overlaid with gold, both "from the house side," as the Hebrew says, and from the outside. The ark was gold, then, as well as wood. The commandments were not to be seen as arbitrary human rules, nor as ways for us to set up an account to gain reward. Commandments are not always verbal rules at all. The symbolic power of an action or of a concrete example speaks aloud in the history of Israel, in God's act to free Israel from Egypt, in the life of Jesus, or in the parables of the Bible. The commandments are the living of God's will, the enjoyment of the Presence of the Lord, letting the Lord's love and mercy be the center and power of life.

The rings and staves were the same combination of wood and gold, of human and Divine. They were to carry that Word of God wherever the people went, into all circumstances and states of life. The rings themselves are the joining of good with truth. The definite command that the poles never be removed from the rings underlines the constant readiness for application to life.

The cover of the ark was of pure gold. This is the "mercy seat," the word for covering over sin or guilt. It is the word "forgive" in Psalm 79:

Do not remember against us the iniquities of our forefathers;

let thy compassion come speedily to meet us, for we are brought very low.

Help us, O God of our salvation, for the glory of thy name;

deliver us, and forgive our sins, for thy name's sake! Ps. 79:8-9

It is the word "atonement" in Israel's Yom Kippur, or Day of Atonement, one of the most sacred of Israel's yearly solemn festivals or "meetings" with God. It is this mercy, this Divine forgiveness, this awareness of God's pure goodness with no evil at all, not remembering past sins against us, which overlies the Word of God's commandments as we take them home to our hearts.

Finally, the two cherubim were of pure gold alone, Cherubim in the ancient Near East were great winged guardian figures, part human, part animal, appearing in carvings on the thrones of kings or at the entrances of palaces or temples. Ezekiel gives a detailed description. In his vision they were

four living creatures . . . they had the form of men, but each had four faces, and each of them had four wings. Their legs were straight, and the soles of their feet were like the sole of a calf's foot; and they sparkled like burnished bronze. Under their wings on their four sides they had human hands . . . their wings touched one another; they went every one straight forward as they went . . . each had the face of a man in front; the four had the face of a lion on the right side, the four had the face of an ox on the left side, and the four had the face of an eagle at the back. ... In the midst of the living creatures there was something that looked like burning coals of fire . . . and the living creatures darted to and fro like a flash of lightning.

Ezek. 1:5-14

Others of these creatures had the body of an ox or lion or bull. The cherubim in Solomon's temple were said to be ten cubits (or about fifteen feet) high (1 Kings 6:23). In one description of the ark, the Lord is seen as enthroned "on the cherubim" (I Samuel 4:4). In the symbolism of Psalm 18 they are associated with the wind,

as God rode on a cherub and flew;

he came swiftly

upon the wings of the wind.

Ps. 18:10

Ezekiel saw them in his vision of God enthroned in the temple. The seraphim of Isaiah's vision of God are probably also these numinous guardian beings (Isa. 6). In Revelation 4 to 6, they are around the throne of God in heaven.

Ezekiel, Isaiah, and Revelation all suggest the mysterious nature of these living creatures, seen indeed, but seen only in vision at the boundary of human sight and where God's Presence or heaven begins. In Genesis 3, after the man and woman had made their choice to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, the LORD God sent them "forth from the garden of Eden . . . and at the east of the garden of Eden he placed the cherubim, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to guard the way to the tree of life" (Gen. 3:23-24). The choice to go the way of human reason, persuasion, and rationalization, is followed by the protection of the way of return to Eden, lest the tree of life be profaned and humankind destroy itself. The cherubim are these mysterious and totally good protecting beings, guardians of the transcendent.

The cherubim are "of one piece with the mercy seat." They spread their wings "above, overshadowing the mercy seat with their wings" of mercy and protection, of support, and of power to rise to the heights. Their faces, turned one to the other, and to the mercy seat itself, speak of love to the neighbor and to God, the Divine Goodness from which they spring.

The inmost of the human mind, that edge of conscious awareness and unconscious creative power, of earthly beings and the Divine, is imaged in the ark with the

cover of mercy and the cherubim above. Here we meet I the Lord. The Lord commands us to prepare the tent of meeting and the ark, in order to meet with us. The inmost mind is not the whole of human awareness. All life depends on God, and the Divine is received in many different ways in different states of being, both consciously and unaware. Yet, that the Divine Presence be received at all, and life on earth continue, there must be somewhere the awareness of that Presence here described.

It is a familiar religious truth that the Presence of the Lord and the awareness of heavenly reality, are not rewards of human intelligence or study. They are gifts given in a setting of trust and mutual love. It is true again that for adults innocent trust and love do not feel entirely natural, but come from the Lord's goodness. Divine goodness, received consciously, is Divine mercy. Such trust and love are the cherubim. "There I will meet with you, and from above the mercy seat, from between the two cherubim that are upon the ark of the testimony, I will speak with you of all that I will give you in commandment for the people of Israel."

The offerings for the tabernacle symbolized the wealth already there within the deep levels of the human mind. The ark of the testimony symbolizes the contact with the Other. This account in Exodus speaks to us of the transcendent power of each reality imaged in the symbols, the gold, the blue, the linen and black wool, and all the materials within, the ark and cherubim, as present now as at any time of ancient origin.

Sit quietly a moment and ask the Lord to be with you as you quiet your mind and prepare to turn to the Word of God.

Read again Exodus 25:10-22 with your mind open to hear it as God's Word to you.

They shall make an ark of acacia wood; two cubits and a half shall be its length, a cubit and a half its breadth, and a cubit and a half its height. And you shall overlay it with pure gold, within and without shall you overlay it, and you shall make upon it a molding of gold round about. And you shall cast four rings of gold for it and put them on its four feet, two rings on the one side of it, and two rings on the other side of it. You shall make poles of acacia wood, and overlay them with gold. And you shall put the poles into the rings on the sides of the ark, to carry the ark by them. The poles shall remain in the rings of the ark; they shall not be taken from it. And you shall put into the ark the testimony which I shall give you. Then you shall make a mercy seat of pure gold; two cubits and a half shall be its length, and a cubit and a half its breadth, and you shall make two cherubim of gold; of hammered work shall you make them, on the two ends of the mercy seat. Make one cherub on the one end, and one cherub on the other end; of one piece with the mercy seat shall you make the cherubim on its two ends. The cherubim shall spread out their wings above, overshadowing the mercy seat with their wings, their faces one to another; toward the mercy seat shall the faces of the cherubim be. And you shall put the mercy seat on the top of the ark; and in the ark you shall put the testimony that I shall give you. There I will meet with you, and from above the mercy seat, from between the two cherubim that are upon the ark of the testimony, I will speak with you of all that

I will give you in commandment for the people of Israel.

let your mind turn to one commandment you hear the Lord speaking to you,Thou shalt love the LORD with all thy heartThou shalt love thy neighbor as thy self Honor they father and thy motherwhatever one it is that comes to you. And now, in your mind, take the tough strength of fine grained acacia wood and make an ark to put the commandment in, a functional, strong wooden chest, with rings, always ready to take that commandment with you as you go in life, to take in intact, that nothing weaken it or destroy its sacredness. I feel the power of that commandment as you let it go with you as you visualize yourself doing what you do in your home, at work, and in the street.

Now take pure gold, of pure love, and cover the strength of the ark of that commandment with mercy, turning your mind to the Lord's goodness going with you, to the Lord's love as the strength of your keeping that commandment, giving the commandment the power of love to be accomplished, and see the Lord's mercy go with you with its power in your home, at work, and in the street.

And now take the pure gold of that cover of mercy and visualize its shining strength form a beautiful, living, winged, protective figure on each end of the cover of mercy, on the edge, the limit, where your ark ends and Heaven begins, and see the power of the hosts of Heaven go with you as you move in the strength of that commandment in your home, at work, and in the street.

Lord, thank you that your mysterious Presence is revealed not to the subtleties of intellect, but to each one who turns in simplicity of heart to know your will, to do it. Thank you, Lord. Amen.

3. Oil for the Lamps

The LORD said to Moses, "Command the people of Israel to bring you pure oil from beaten olives for the lamp, that a light may be kept burning continually. Outside the veil of the testimony, in the tent of meeting, Aaron shall keep it in order from evening to morning before the LORD continually; it shall be a statute for ever throughout your generations. He shall keep the lamps in order upon the lampstand of pure gold before the LORD continually."

Leviticus 24:1-4.

According to the rabbis, Israel saw a depth in God's goodness to them in the fact that God not only created and loved them, but also told them through the Scriptures about that creation and that love, so they would know it consciously. So the tabernacle and the ark within it symbolize the dwelling place where the Divine is not only present, but where the Divine Presence is known. The light that sheds this knowledge is the subject here.

People can look on the same thing in very different lights. A child may see in grass and flowers their pleasantness to touch and smell with his bare feet and nose.

A farmer may see them as food for cattle, a botanist as instances of species differentiation. An adult absorbed in other interests may not see them at all. A war may look in one light brilliant and glorious, in another horrible and wrong in its cost in human suffering, in another painful but necessary as a step toward justice. The prophets and the psalms ask us the question: In what light does God see our history and our world? What would it be like to see in the light of goodness and truth itself, the light of the Lord's own mercy and power to heal? To make love the basis for wisdom?

The light for the tabernacle was from oil of olive, pure, and beaten. The oil is the symbol for love, associated with joy, with the touch of healing, and with the anointing of a priest or king. It symbolizes heavenly Divine good. The word "Messiah" means literally "anointed with oil." The two olive trees on either side of the lampstand in Zechariah's vision, are the two Messiahs, or literally in Hebrew, "the sons of the olive" (Zech. 4:14). The Messiah is love giving light to the world, and John speaks often of that light as he sees Jesus as Messiah: "I am the light of the world; he who follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life" (John 8:12).

When the people brought the oil, Aaron was to set the lamps in order outside the veil of the testimony in the tent of meeting. People are needed to beat swords into ploughshares, or to beat olives in a press or mortar, into pure, fine oil. People who have done the beating see their ploughshare or their oil with respect, and the people were to bring their beaten oil and make the lampstand of pure gold, as they had the cover, the cherubim, and the fittings for the ark. The stand held seven lamps of gold, and these were to be kept filled and burning from evening to morning every night, making light continually.

The people have a necessary part here. But the references to Aaron and to the curtain between the ark of the testimony and the lamps, show that we are dealing with more than the ordinary conscious level of the people's experience. Aaron is the priest. As Moses symbolizes a truth that cannot be heard or perceived directly, Aaron is the teaching of good and truth in a form that people can hear. The priest, the spokesman and teacher, represents the Lord's love of saving, the part in us that mediates, explains, and loves to save, that draws us to the Lord.

Aaron is the one to "keep the lamps in order . . . before the Lord." The word "order" here is used elsewhere for Living a table for a meal (Isa. 21:5), drawing up troops in strategy for battle (Ju. 20:22; I Sam. 17:8), or setting an argument in order for a legal case (Job 13:18). It is the priest in us, and not the trickster, the debater, or the seeker after personal reputation who is there to mediate, to order the strategy of our understanding as we begin to bring our holy things to consciousness.

The lamps were outside the veil of testimony. Inside was only the ark with the Word itself, that inmost Presence of the Lord where the power is known at a level too deep for words or conscious apprehending. The part of the tent of meeting outside the veil is the interpretation of the Presence in relation to the motives and the choices of human life. It is here that the light comes, within the specific context of living what is good or true, m the limits of an existing situation. The inmost truth is always too much, too powerful, to be contained within our limits. But unless the attempt is made to see its interpretation within the limits, it does not come to light and life at all. So we are asked to bring our oil, that love may be the light in which we see the things of God; but we are asked also to respect the veil between the lighted and the inmost ways of knowing. On this boundary of conscious and unconscious we need our Aaron as spokesman for our Moses.

Psychologists since the 18th century have made us all aware of the power of the unconscious. Jung saw the Ego and the consciousness as a small segment of the person, as compared to the personal, and then to the collective unconscious.' The Ego with its conscious analysis of itself and others, its carefully preserved image of itself which it shows to the world in interactions with people, and even its areas of personal unconscious, the feelings and the unseen motivations relating to its personal world, is still not the larger segment of the person. The anima or animus which the man or woman can come to know as inner partner, that other side with which he or she functions as a whole person, and the collective unconscious, make up by far the larger segment. It was in this larger segment of the person that Jung found the Self, the deep identity, the center of our real decisions, of which the conscious, Ego choices are the afterthoughts.

Jung saw religious sacraments and symbols as "wise and appropriate" means for dealing with these unconscious powers.2 He encouraged his patients to find and use their individual religion in coming to their awareness of their deep Self and finding a sense of meaning in their existence.3 Jung criticized traditional religion, however, for its rigidity and its failure to let the power of symbol live and reach maturity in individual Selves.

We have been following Swedenborg's approach to the Bible in this treatment of the tabernacle. Swedenborgians, like members of any religious group, succumb, of course, in many ways to the temptation of rigidity in religion. But Swedenborgians have a strength in their respect for the power of symbol. For them, the collective unconscious is the world of spiritual reality through which Divine love and wisdom reach humankind and without which we would die. For them, the power of symbol is the power that creates the universe, now as in the past, as each person seeks to realize that Self that is in the process of creation, and learns to be a functional form of love, and sees in the amazing reality of the human being himself or herself the pattern of the universe. For them, too, the Self is in the larger segment, not in the area of the conscious Ego. The Self gains strength from its membership in the spiritual world, as it finds more and more its own distinct identity and its relationship with the Divine. And for Swedenborgians, these Biblical narratives of the tabernacle and the ark can bring awareness of that membership. The narratives are living Word of God, not only in their literal history, but as each person comes to meet the symbols in them, and lets the symbols come alive. And the literal history itself is a symbol of the spiritual journey of every man and every woman.

The light of the tabernacle is the symbol of our bringing to consciousness the inner, deeper meaning of God's Word for us. In our lives we encounter lights of many shades and colors. This light of the tent of meeting is what we have felt of the Lord's own love, the Good itself. We bring the oil, for all our love is from the Lord, really ours because it is a gift, really given. We bring the oil for the lamps to bring to light for us the reality of that dwelling place of God with us, including the reality of the veil. And if in some way we get used to seeing in that light, to any degree at all, we find increasing strength in awareness that the depths within us are potentially powers for good. For all the creative momentum of the universe supports our finding of our deep distinct identity in the world of which God is ultimately the light.

What would it be like to see, and then to walk, in the light of the Lord's mercy and healing power?

Sit quietly a moment. Visualize for a moment the lamps before the veil that hides the ark. Feel the difference of that inner, timeless world behind the lamps and veil, from the outer world of physical things and busyness in time.

Now open your inner eyes and ears again as you read again Leviticus 24:1-4, and let its symbols be a way for God to speak to you.

The LORD said to Moses, "Command the people of Israel to bring you pure oil from beaten olives for the lamp, that a light may be kept burning continually. Outside the veil of the testimony, in the tent of meeting, Aaron shall keep it in order from evening to morning before the LORD continually; it shall be a statute for ever throughout your generations. He shall keep the lamps in order upon the lampstand of pure gold before the LORD continually."

Visualize the clear, golden olive oil, pure oil of love, of joy, of healing, of anointing priests and kings, givings its light in that part of life that you can see, that part which is separated only by a veil from the reality of Love itself in all its power. Rest for a moment in the joy of being in the light of Love itself. Feel the warmth and the power of that light pouring down upon you, surrounding you with good.

And now turn your mind to some decision you have to make, or some person with whom you have a relationship, and see that decision or that person in the light of Love itself. Feel the warmth and the power of that light pouring down upon that decision or that person, surrounding it or him or her with good. And now let go, and let the power of the Love work, and see your decision or your person in that light, and be thankful. (Note: If you are dealing with a person, and if the person who comes to mind is one with whom you have tension or hostility, you may want to start this exercise with someone else first, someone you feel positive about. Try it with the easier person first, and only then with the more difficult case. In either case, let go. Don't try to force a result. Let the light of Love work, and be thankful.)

Lord, thank you that your Love is so close to us, your love so amazing, so real I cannot imagine, much less see it, there every moment, in all the power that makes the universe, coming in goodness unto me. Thank you, Lord. Amen.

1

Joseph Goldbrunner, Individuation (Notre Dame, Indiana: Univerity of Notre Dame Press, 1964), Diagram, p. 124. 2 Ibid., p. 166. 3 Ibid., pp. 169, 170.4. The Altar of Sacrifice

An altar of earth you shall make for me and

sacrifice on it your burnt offerings and your peace offerings, your sheep

and your oxen; in every place where I cause my name to be remembered I will

come to you and bless you. And if you make me an altar of stone, you shall

not build it of hewn stones; for if you wield your tool upon it you profane

it.

An altar of earth you shall make for me and

sacrifice on it your burnt offerings and your peace offerings, your sheep

and your oxen; in every place where I cause my name to be remembered I will

come to you and bless you. And if you make me an altar of stone, you shall

not build it of hewn stones; for if you wield your tool upon it you profane

it.

Exodus 20:24-25.

We have seen three essential elements in Israel's tabernacle: the offerings of the materials for it to be built at all, the making of the ark to receive the Word of God, and the lighting of the lights to let the whole be seen. These things are real. But they are certainly not the whole of anyone's inner life. They are the good side. And as I think of them, and think of letting them come into my inner life with power, I find another side of me that also needs to be heard.

The wealth of materials for a tabernacle, the ark of the Word of God, and the light of Love itself from the Presence of God? That doesn't feel like what's in me. The things I notice are the strangest combinations of fears and hurts and weird, embarrassing memories, some joys and hopes, some wants and worries, some plans, and some plain, blind panic. I do sometimes have a sense of peacefulness or beauty, or awe that I am alive at all, and, yes, sometimes when I need it a strength that gives me courage. But usually it's the strange things, and I have the feeling that if I open the door to them, all sorts of horrible, worse things will come. Even if that holy center is there, how in the world can I get what's in my mind to come near it? And is it safe?

And so I know that if the dwelling place of God is to be real for me, it won't always be easy. It feels frightening and painful to deal with those things, even though I tell myself the pain is a pain of growth. But no significant journey is always easy. And I know it is my journey. The choice to do it and the timing of it, are mine. And so I am ready to go on and ask the Lord how to come near the Presence of God within in ways that lead to healing and not to hurt.

But the first step in coming near is building an altar of sacrifice. And instantly my mind begins to bring up its objections. Now, wait a minute. Killing animals on altars doesn't sound like a very promising start. Those verses in Exodus are grim. What possible use can those instructions be to me? Haven't we learned beyond all doubt that God asks no such thing? We know the Lord desires "mercy and not sacrifice, knowledge of God more than burnt offerings." (Hos. 6:6). "To do justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly" with God has always meant more than "thousands of rams or ten thousands of rivers of oil." (Mic. 6:6-8). Obviously, such sacrifices have never been what God really wanted of people, and they aren't now. God does not desire death and pain, and God has not changed.

These questions are valid and cannot be left without response. A first step is to consider the meaning of sacrifice for ancient Israel. For us today, the word "sacrifice" has almost entirely negative connotations: "to offer to God, to give up, destroy, permit injury or forego a valued thing for the sake of something of greater value, to sell at less than the supposed value," according to Random House. The root meaning of the word, however, was its meaning for Israel. They meant quite literally to "make holy" (sacer and facere), to bring to God, and usually with great joy.

Some sacrifices were wholly give to God as burnt offerings which went up in flames. The far more common thing to do with sacrifices, however, was to eat them. This was the rule with the peace offerings. Ancient Israel lived mainly on the milk and cheese of sheep and goats, and then, later on, of larger cattle, as they settled and began to raise crops. To kill one of those animals for food was for a rare occasion only, a special guest meal or celebration, a yearly family gathering (I Sam. 20:6), a fulfillment of a vow or giving of thanks (Ps. 116:17f), or a coronation (I Sam. 11:15). When Israel went to Gilgal to crown Saul king, "they sacrificed peace offerings before the LORD, and there Saul and all the men of Israel rejoiced greatly" (I Sam. 11:15). Another time, Samuel, the seer, went to a high place to "bless the sacrifice," to which some thirty people had been invited, and persuaded Saul to stay and eat a special portion of the meat as an extra guest (I Sam 9:13-24). A key word at these festival meals is "rejoice," and Israel's celebration of any public worship was in Hebrew called typically "rejoicing" before the Lord their God (Dt. 16:11).

All eating of meat involves sacrifice, the giving of one life that another may live. Some religions have responded to this with abstinence from meat, and others with the reminder that all eating of any food is to be done reverently as worship. Israel's response accepted the distinctiveness of the eating of meat, and asked a special reverence at any accepting of another breathing "soul of life" (Gen. 1:24) for food. This response symbolized, at least in part, sharing in a common life with all creatures who have breath, and realizing that we continue in life only through receiving it from others.

Israel's kosher meat observance is a literal reminder of this attitude to life. The life of an animal is its blood as well as its breath. And so, according to the tradition, when after the flood mankind took the step that separated them from their original membership in the family of moving, breathing creatures when all lived peacefully on green plants, the one part of the animal not to be eaten, was the blood. Blood and breath were too holy, too closely connected with the original gift of life, and the blood was to be poured out to God, the giver of life. So God blessed Noah, and said

Every moving thing that lives shall be food for you; and as I gave you the green plants, I give you everything. Only you shall not eat flesh with its life, that is, its blood. For your lifeblood I will surely require a reckoning; of every beast I will require it and of man. . . . Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed; for God made man in his own image.

Gen. 9:3-6

In Israel's sacred eating of meat, then, the blood was sprinkled on the altar, the fat and kidneys burned upon it, the breast and right thigh especially handled, the thigh given to the priest, and the remainder returned to the man who offered it as a feast for him and his friends. In this slaughtering of the animal there was the relinquishing of one's own proprietorship, the acknowledgment that all life is a gift. The feast became a feast from the Lord, which otherwise might have been mere enjoyment of one's own good things. To eat our life food in this manner is to hallow the actions of our lives, not doing them from habit or necessity or as our own empty pleasure, but "rejoicing before the Lord," living new life freely in what we do. The Lord's word about sacrifice in this passage in Exodus does not ask an arbitrary work of supererogation in coming to the Holy Place. It asks that we bring the substance of our actual lives to the Lord, to be touched and to be hallowed.

Samuel went to a "high place" to consecrate the sacrifice. An altar is typically raised up, a spiritual high place, as opposed to a depression. It might be raised of earth or of stones. Good earth receives seeds and brings forth fruit. It is our longing for goodness that we raise before the Lord, the certainty that all goodness has its source in the Lord, and the desire to do that goodness. Once there, it remains a height in the mind, a place of sureness and perspective as we go down from it to work or return to it for direction.

Stones, on the other hand, are firm truths that do not shift around. Some people work more naturally from good or feeling and receiving, and others from truth or searching and understanding. There is no value judgment here. Some can build an altar of stones more easily than one of earth. The only provision for the stones is that we accept each stone in its wholeness, and do not hew it to our own devices. The essential for the altar is not that it be earth or stones, but that it be real and of our building. To demand immediate demonstration of feeling from those who need to work first in thought, is inconsiderate and frightening. To demand words from those who need to live first with feeling states or intuitive awareness, is hopeless and frustrating. Worship, like love, is comfortable in an atmosphere of appreciation for what each person offers freely and with integrity; it is uncomfortable with demands laid on arbitrarily from outer space. Either altar is good. Either needs only to be raised in the heart whose altar it is.

The animals to be offered are our affections, our feelings for what we desire as good. Animals have a strange power to engage our feelings. Visualize for a moment a cat, a lion, a snake, a lamb. Each brings out a different and quite distinct response, a quality in us that needed only the symbol to come alive. That spark of identification with the cat's distinctive kind of playfulness, combined as it is with a readiness to pounce, is that little leap or tug inside us in response. So all animals symbolize feelings, some wild, some tame, all powerful, but not in a language we understand in words.

The animals Israel brought regularly to the altar were from their flocks (sheep, lambs, goats, or kids), that is innocence and love in the inner person, or the bigger work animals of their herds (oxen, bullocks, and calves), that is feelings for good and truth in the external person in action in the world. These feelings are the power behind all our inner states, all our relationships, and all our actions. New life here, renewing love from God, is mercy and knowledge of the Lord, in which the Lord does indeed come near and bless the life brought near for hallowing. For that is what blessing is: "that which has within it being from the Divine" (AC 8939).1 And all we have said about Israel's use of the altar of sacrifice, has to do with awareness of that which is of God in all of life.

All this is very beautiful, but we have not yet responded to one of our original questions. It is, after all, a "slaughter altar." How does the pain of death fit with what we have been saying? This question is real. The animal we eat does die, and Israel had not yet hidden that fact under the plastic wrappers of the supermarket. To know that what sustains my life is a gift, not mine until I release it and receive it again, to give up my proprietorship, is to experience a dying. True, the flame on the altar is the Love of God in all its light and heat and life. But that flame asks all of me if I am to let it touch my life. To receive my life again in freedom, I must first have given it up. I cannot even approach that Love without being deeply and even desperately conscious of the evil in my own heart. For me as an adult, the innocence with which the Lord unites is the innocence of repentance, of turning back to the Lord as the source of my life.

Death is part of sacrifice. For the Christian, the sacrifices of Israel prefigure that one most significant death, Jesus'. But if we respect Israel's use of sacrifice, this is not in the negative sense of an arbitrary loss, a negative bargain struck with God or a penalty paid for a fault. It is in the sense of a life in which the Love of God comes to us where we are, gives itself to us, touches us, hallows us, and makes us come alive if we give ourselves up to it.

Giving is not without its consequences. There is no coming to the light of that flame that does not show up vividly the weird, and even more weird and unexpected, as well as the deeply satisfying elements in my inner life. Israel made offerings for sin, defilement, and trespass, as well as for thanksgiving, and knew that these too were part of them and had their place in worship. We will be dealing with them later and with the issue of pain and death. The first step is to know that there is the Holy Place within, that God's presence is with us to touch the depths of our feelings and of our awareness. But, clearly, this Place will not be functional for us until we bring the feelings to the altar, the actual underlying feelings, whatever they are, that make us do the things we do. But, again, in the very awareness of the strangeness of what we have to bring, the light of the Presence is already working; and the power, the living energy of that light is Love.

Think back for a moment on the wonder of a holy place within you where God dwells with you. Really with you. Not with the front you take to church or lay out there for the public. But with you, with those fears, hurts, memories, joys, hopes, worries, plans, panics, strengths, and sometimes awe.

Turn to God's Word, and read the meditation Psalm 139:

O LORD, thou hast searched me and known me! Thou knowest when I sit down and when I rise up;

thou discernest my thoughts from afar. Thou searchest out my path and my lying down,

and art acquainted with all my ways. Even before a word is on my tongue, lo, O LORD, thou knowest it altogether.For thou didst form my inward parts,thou didst knit me together in my mother's womb. I praise thee, for thou art fearful and wonderful.Wonderful are thy works! Thou knowest me right well;my frame was not hidden from thee, when I was being made in secret,intricately wrought in the depths of the earth. Thy eyes beheld my unformed substance;in thy book were written, every one of them, the days that were formed for me,when as yet there was none of them. How precious to me are thy thoughts, O God!

How vast is the sum of them! If I would count them, they are more than the sand. When I awake, I am still with thee.Before that thought had reached the conscious verbal state of being on your tongue, God knew it altogether. Before any inner part of you had come to birth at all, God knew it. And, knowing all of what you are, God gave you life and brought you to birth and into being. What is the strangest thought or fear that might come in that strange country of your mind? God knows it altogether, and still is there.

Now read again Exodus 20:24-25, and hear God's Word addressed to you to come, to build your altar, to bring your feelings as they are, to receive your life from God, and to be blessed.

An altar of earth you shall make for me and sacrifice on it your burnt offerings and your peace offerings, your sheep and your oxen; in every place where I cause my name to be remembered I will come to you and bless you. And if you make me an altar of stone, you shall not build it of hewn stones; for if you wield your tool upon it you profane it.

Lord, thank you that you know me better than I know myself, and still you ask me to raise my thoughts or feelings to be an altar for you to come to give me blessing. Thank you that the sacrifice you want is not some punishment for guilt, or game of saying the right words, or proving worthiness, or bargaining for the right favor for some move ahead, but simply coming, as I am, to you who know me, to let your love touch me and to receive the gift of life. Thank you, Lord. Amen.

1

Emanuel Swedenborg, Arcana Coelestia (New York: Swedenborg foundation, Inc.) Par. #8939.5. Bread and Incense

When any one brings a cereal offering as an

offering to the LORD, his offering shall be of fine flour; he shall pour oil

upon it, and put frankincense on it, and bring it to Aaron's sons the

priests. And he shall take from it a handful of the fine flour and oil, with

all of its frankincense; and the priest shall burn this as its memorial

portion upon the altar, an offering by fire, a pleasing odor to the LORD.

And what is left of the cereal offering shall be for Aaron and his sons; it

is a most holy part of the offerings by fire to the LORD. . . . You shall

season all your cereal offerings with salt; you shall not let the salt of

the covenant with your God be lacking from your cereal offering; with all

your offerings you shall offer salt.

When any one brings a cereal offering as an

offering to the LORD, his offering shall be of fine flour; he shall pour oil

upon it, and put frankincense on it, and bring it to Aaron's sons the

priests. And he shall take from it a handful of the fine flour and oil, with

all of its frankincense; and the priest shall burn this as its memorial

portion upon the altar, an offering by fire, a pleasing odor to the LORD.

And what is left of the cereal offering shall be for Aaron and his sons; it

is a most holy part of the offerings by fire to the LORD. . . . You shall

season all your cereal offerings with salt; you shall not let the salt of

the covenant with your God be lacking from your cereal offering; with all

your offerings you shall offer salt.

Leviticus 2:1-3, 13

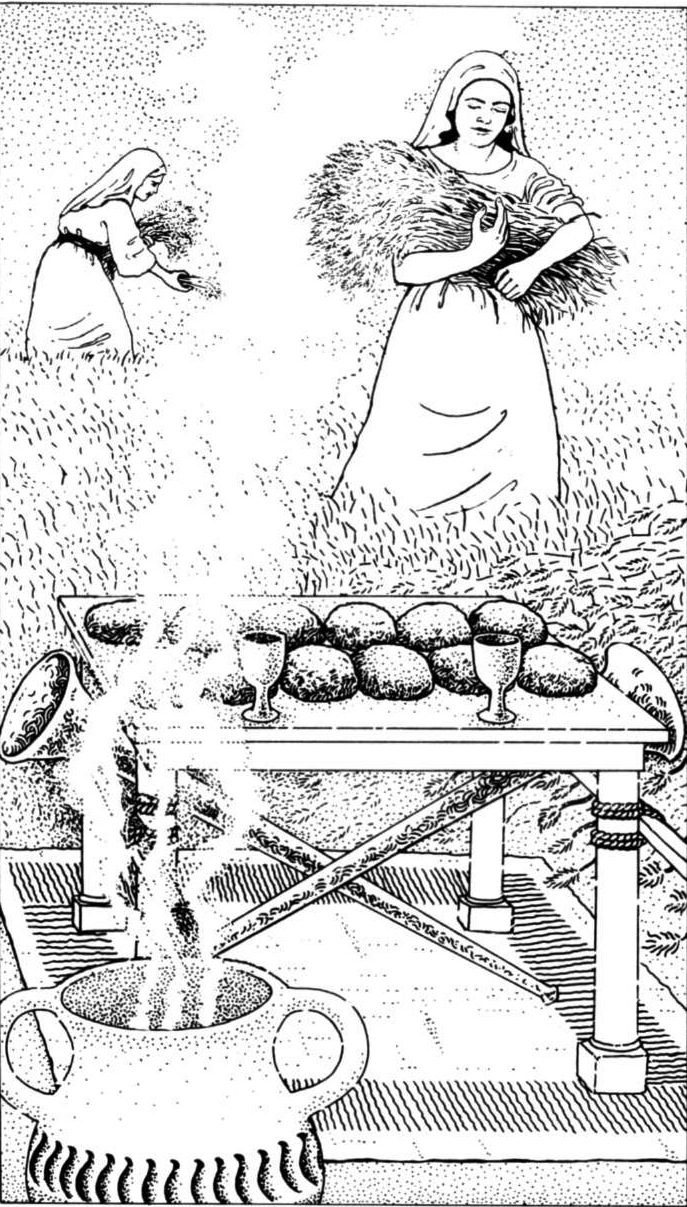

The altar of sacrifice was a way of bringing deep, underlying feelings, painful as well as joyful, to the Presence, as these feelings were aroused usually by some special occasion of personal, family, or national life. There was something of crisis in this slaughter altar, standing as it did in the courtyard, outside the holy place itself, bearing the fire that made present Love itself. The lampstand of pure gold with its lighted lamps, within the holy place, but still, of course, outside the veil, also had a sense of otherness about it. It pointed beyond what human eyes can see to Truth itself. Both of these furnishings were awesome witness to the Presence in its dwelling place within. The awe is real. But the holy place had also another, more homely and more comfortable symbol of coming into God's presence: the table for the loaves of bread.

The table again was of pure gold in witness to God's love, but the loaves, baked regularly of fine flour grown and ground by people, were the peaceful satisfactions of daily receiving love and strength from God in the normal affairs of life and especially in daily work.

Eating food is perhaps the one most basic symbol of needing to be nourished, to be sustained in life. The prophet Joel sees food as parallel to "joy and gladness" in the "house of our God" (Joel 1:16). The mother who nurses and comforts her child, and the Lord who says to his disciple, "Feed my sheep," are two vivid images of God's caring love in the Bible (Isa. 66:12; John 21:7). To give and share food is the simplest, most natural act of human caring, and at the same time the most directly open to the Divine. It was the way of sharing in the most solemn act of communion in the ancient Near East, as well as the way of fulfilling the most basic human obligation: hospitality to the stranger. According to the earliest tradition, when Moses and Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and seventy of the elders of Israel saw the God of Israel at that most solemn time of the making of the covenant, "they beheld God, and ate and drank" (Ex. 24:11). Again, when the Lord came to speak with him at Mamre, Abraham's first words to his angel visitors were an embodiment of the right ethical response to guests: offering food.

When he saw them, he ran from the tent door to meet them, and bowed himself to the earth, and said, "My lord, if I have found favor in your sight, do not pass by your servant. Let a little water be brought, and wash your feet, and rest yourselves under the tree, while I fetch a morsel of bread, that you may refresh yourselves, and after that you may pass on-since you have come to your servant."

Genesis 18:2-5

When the angels stayed, the "morsel of bread" became, of course, a meal of meat and curds and milk as well as cakes of fine meal. This is partly normal Near Eastern hyperbole, as any ancient or modern Israeli, Arab, or Greek might speak of what he would set before a guest. But it is also true that bread is the common, staple food, the symbol for all food in general, for all that nurtures and satisfies, including the celestial food of God's love for humankind, and human love to the neighbor. According to Swedenborg, bread is love brought to its simplest, most basic form, on earth and with each person, as well as in heaven (AC 2177). The table for the loaves of bread means bringing normal, human daily work to the Lord's Presence to find peaceful satisfaction in it.

What is in agreement with our life is food for us, and satisfies. Some satisfactions are more tense than others, however. To gain immediate satisfaction only, no matter what the consequences to others, brings fear of retaliation. To hold on to inflated or temporary satisfaction, brings fear of loss. So Aaron, the priest in us, who desires our peace, puts our loaves in order each week for the sabbath, as he does our lamps each day.

The greater part of daily work is not made up of spontaneous acts of affection. Work requires thoughtful effort. It requires planning for what will happen, allowing for contingencies, evaluating methods. The mentality which apparently serves work best is used to taking responsibility, depending on its own resources, judging success or failure in terms of outside standards, putting personal needs aside, our own and sometimes those of others, in order to get the job done. Tensions over performance, or over meeting others' standards, are so common they almost seem to be part of having a job. This mentality may seem perhaps most apt to set us on our own, apart from God. The powerful emotions, anger, fear, or love, touch us enough to drive us to our depths, to meet our Lord. This work mentality seems just to separate. But if persons can find no peace or sense of meaning in the work that takes the major part of their days and greatly influences their feelings about themselves, then something is missing in their tabernacle. It is good to be reminded, when we get pulled off base by regular or by other demands on our time, that one element even now functioning in our inner self, is the priest within, who has the desire, the energy, and the skill to order our priorities so that we may find peaceful satisfaction.

Israel's tabernacle provided ways to deal with both the regular and the occasional demands of work. For the regular, the loaves were set in order every week on the table in the holy place. For the occasional, special bread offerings were brought to the altar in the courtyard as needed. For both, the bread was to be of fine flour. Work takes many forms. It may be public service, or highly public leadership at the executive level, flying airplanes, or repairing their engines, writing books, or washing floors. For some, it may be dealing with inability to get a job. For some, it may be work never acknowledged as work at all, hard work of planning, marketing, cooking, cleaning, driving, washing, teaching, but taken for granted because it is expected of a mother or a father. What makes it "fine" is not its public image or prestige, but its motivation and its actual use to persons in society.

Each kind of work involves some kind of value, or it would not be done at all. It may provide a living, foster an enormous ego, be the facade for rebellion against a parent, or be a sensitive way of serving God and coming alive oneself by using one's best talents to contribute creatively to the common good. Negative, or hidden motivations can create problems. But the work mentality itself can also split our calculating self from our essential feelings and splitting thought from feeling is destructive. Neither accumulation of data or of accomplishments without feeling, nor spontaneously fluctuating expression of every feeling felt, without thought for consequences, makes fine flour. Work done intelligently and from a spirit full of the Lord, wise thought for others and for oneself, put into action, is the flour for these loaves of bread.

To the flour, oil was added. If fine flour is needed for this bread, it is no wonder that pure olive oil, symbolizing God's mercy, is needed too. All life and wisdom and love are, of course, from God, as well as all good food and grain. But specific knowledge of God's mercy to all is essential to the sense of the Lord's presence for our good.