| Previous: 4. The Altar of Sacrifice | Up: THE HOLY CENTER | Next: 6. Mornings and Evenings |

5. Bread and Incense

When any one brings a cereal offering as an

offering to the LORD, his offering shall be of fine flour; he shall pour oil

upon it, and put frankincense on it, and bring it to Aaron's sons the

priests. And he shall take from it a handful of the fine flour and oil, with

all of its frankincense; and the priest shall burn this as its memorial

portion upon the altar, an offering by fire, a pleasing odor to the LORD.

And what is left of the cereal offering shall be for Aaron and his sons; it

is a most holy part of the offerings by fire to the LORD. . . . You shall

season all your cereal offerings with salt; you shall not let the salt of

the covenant with your God be lacking from your cereal offering; with all

your offerings you shall offer salt.

When any one brings a cereal offering as an

offering to the LORD, his offering shall be of fine flour; he shall pour oil

upon it, and put frankincense on it, and bring it to Aaron's sons the

priests. And he shall take from it a handful of the fine flour and oil, with

all of its frankincense; and the priest shall burn this as its memorial

portion upon the altar, an offering by fire, a pleasing odor to the LORD.

And what is left of the cereal offering shall be for Aaron and his sons; it

is a most holy part of the offerings by fire to the LORD. . . . You shall

season all your cereal offerings with salt; you shall not let the salt of

the covenant with your God be lacking from your cereal offering; with all

your offerings you shall offer salt.

Leviticus 2:1-3, 13

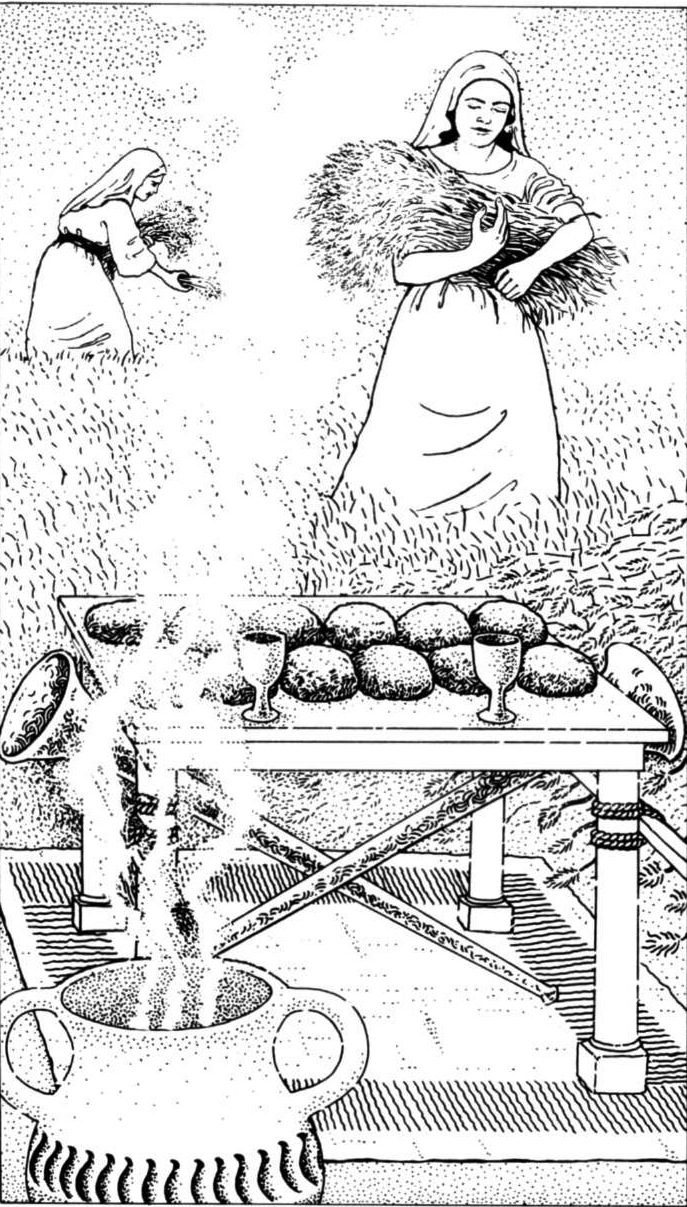

The altar of sacrifice was a way of bringing deep, underlying feelings, painful as well as joyful, to the Presence, as these feelings were aroused usually by some special occasion of personal, family, or national life. There was something of crisis in this slaughter altar, standing as it did in the courtyard, outside the holy place itself, bearing the fire that made present Love itself. The lampstand of pure gold with its lighted lamps, within the holy place, but still, of course, outside the veil, also had a sense of otherness about it. It pointed beyond what human eyes can see to Truth itself. Both of these furnishings were awesome witness to the Presence in its dwelling place within. The awe is real. But the holy place had also another, more homely and more comfortable symbol of coming into God's presence: the table for the loaves of bread.

The table again was of pure gold in witness to God's love, but the loaves, baked regularly of fine flour grown and ground by people, were the peaceful satisfactions of daily receiving love and strength from God in the normal affairs of life and especially in daily work.

Eating food is perhaps the one most basic symbol of needing to be nourished, to be sustained in life. The prophet Joel sees food as parallel to "joy and gladness" in the "house of our God" (Joel 1:16). The mother who nurses and comforts her child, and the Lord who says to his disciple, "Feed my sheep," are two vivid images of God's caring love in the Bible (Isa. 66:12; John 21:7). To give and share food is the simplest, most natural act of human caring, and at the same time the most directly open to the Divine. It was the way of sharing in the most solemn act of communion in the ancient Near East, as well as the way of fulfilling the most basic human obligation: hospitality to the stranger. According to the earliest tradition, when Moses and Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and seventy of the elders of Israel saw the God of Israel at that most solemn time of the making of the covenant, "they beheld God, and ate and drank" (Ex. 24:11). Again, when the Lord came to speak with him at Mamre, Abraham's first words to his angel visitors were an embodiment of the right ethical response to guests: offering food.

When he saw them, he ran from the tent door to meet them, and bowed himself to the earth, and said, "My lord, if I have found favor in your sight, do not pass by your servant. Let a little water be brought, and wash your feet, and rest yourselves under the tree, while I fetch a morsel of bread, that you may refresh yourselves, and after that you may pass on-since you have come to your servant."

Genesis 18:2-5

When the angels stayed, the "morsel of bread" became, of course, a meal of meat and curds and milk as well as cakes of fine meal. This is partly normal Near Eastern hyperbole, as any ancient or modern Israeli, Arab, or Greek might speak of what he would set before a guest. But it is also true that bread is the common, staple food, the symbol for all food in general, for all that nurtures and satisfies, including the celestial food of God's love for humankind, and human love to the neighbor. According to Swedenborg, bread is love brought to its simplest, most basic form, on earth and with each person, as well as in heaven (AC 2177). The table for the loaves of bread means bringing normal, human daily work to the Lord's Presence to find peaceful satisfaction in it.

What is in agreement with our life is food for us, and satisfies. Some satisfactions are more tense than others, however. To gain immediate satisfaction only, no matter what the consequences to others, brings fear of retaliation. To hold on to inflated or temporary satisfaction, brings fear of loss. So Aaron, the priest in us, who desires our peace, puts our loaves in order each week for the sabbath, as he does our lamps each day.

The greater part of daily work is not made up of spontaneous acts of affection. Work requires thoughtful effort. It requires planning for what will happen, allowing for contingencies, evaluating methods. The mentality which apparently serves work best is used to taking responsibility, depending on its own resources, judging success or failure in terms of outside standards, putting personal needs aside, our own and sometimes those of others, in order to get the job done. Tensions over performance, or over meeting others' standards, are so common they almost seem to be part of having a job. This mentality may seem perhaps most apt to set us on our own, apart from God. The powerful emotions, anger, fear, or love, touch us enough to drive us to our depths, to meet our Lord. This work mentality seems just to separate. But if persons can find no peace or sense of meaning in the work that takes the major part of their days and greatly influences their feelings about themselves, then something is missing in their tabernacle. It is good to be reminded, when we get pulled off base by regular or by other demands on our time, that one element even now functioning in our inner self, is the priest within, who has the desire, the energy, and the skill to order our priorities so that we may find peaceful satisfaction.

Israel's tabernacle provided ways to deal with both the regular and the occasional demands of work. For the regular, the loaves were set in order every week on the table in the holy place. For the occasional, special bread offerings were brought to the altar in the courtyard as needed. For both, the bread was to be of fine flour. Work takes many forms. It may be public service, or highly public leadership at the executive level, flying airplanes, or repairing their engines, writing books, or washing floors. For some, it may be dealing with inability to get a job. For some, it may be work never acknowledged as work at all, hard work of planning, marketing, cooking, cleaning, driving, washing, teaching, but taken for granted because it is expected of a mother or a father. What makes it "fine" is not its public image or prestige, but its motivation and its actual use to persons in society.

Each kind of work involves some kind of value, or it would not be done at all. It may provide a living, foster an enormous ego, be the facade for rebellion against a parent, or be a sensitive way of serving God and coming alive oneself by using one's best talents to contribute creatively to the common good. Negative, or hidden motivations can create problems. But the work mentality itself can also split our calculating self from our essential feelings and splitting thought from feeling is destructive. Neither accumulation of data or of accomplishments without feeling, nor spontaneously fluctuating expression of every feeling felt, without thought for consequences, makes fine flour. Work done intelligently and from a spirit full of the Lord, wise thought for others and for oneself, put into action, is the flour for these loaves of bread.

To the flour, oil was added. If fine flour is needed for this bread, it is no wonder that pure olive oil, symbolizing God's mercy, is needed too. All life and wisdom and love are, of course, from God, as well as all good food and grain. But specific knowledge of God's mercy to all is essential to the sense of the Lord's presence for our good.

To fine flour and oil, is added the frankincense of intelligent gratitude. It is hard to think of a more pleasant fragrance than that of freshly baked bread, but the fragrances of spices for anointing oil and for incense were also part of the atmosphere of the tabernacle and of worship. Odors have to do especially with perception, and the pleasant odors of incense with grateful, joyful perception of truth. The underlying nature of a person corresponds closely to the atmosphere in which he or she can breathe easily, and to what odors he or she finds pleasant. Pure frankincense is inmost truth, clarified from the falsity of evil, and perceived with joy. Frankincense was a part of the special combination of spices used to make the cloud of incense always before the ark in the tent of meeting, a special combination sacred to that purpose, and never to be used by human beings themselves (Ex. 30:34-38). Frankincense alone was used by human beings, however, and was associated with the luxury of King Solomon (Song of Songs 3:6), the fragrance of the beloved, the bride to be (Son of Songs 4:14), or, together with gold, as a symbol of the wealth of all the world of nations brought in praise of God to Jerusalem (Isa. 60:6). The odor of frankincense mingled with that of fresh bread, was indeed joyful perception of God's goodness in all,that is, worship.

The bread was also to have salt. The salt of the covenant of God (see Num. 18:19 and II Chr. 13:5) is the desire which love has for wisdom, to do good wisely, and the desire which wisdom has for good, to live and to be fruitful. It is the element that makes heavenly food savory and assimilates it to life. To be without it, is to know truth and have no care for living it, to have no savor.

The bread of regular, daily work was to be twelve loaves of generous size, after the number of all the tribes of Israel, and of the fruits of the tree of life, to represent all the varieties of joy and satisfaction of working with the Lord, conscious of the Lord's presence and purpose. The twelve loaves were in two piles of six, six being the number of work days and representing the full state of labor. The two piles of six, side by side, symbolized the Lord's blessing given equally to those who sought to do what was true or right and to those who sought to do what was good. This was the "show bread," the bread of the Presence, placed by the priest on the table within the holy place for each sabbath. The word for "show" or "Presence" here is literally "faces," that is, before the face of God, that is, in the presence of all that is from the Divine Love, such as innocence, peace, joy, or heaven itself with those who receive it (AC 9545-6).

Loaves could also be brought to the altar to be offered for special needs connected with daily work. The bread of occasional, varied kinds of work might be cakes baked outside the oven and simply anointed with oil (lesser, external duties, subordinate to our chief work), or hastily cooked on a griddle or boiled in a pot like dumplings (incidental duties of all kinds), or even flour ready for the baking (a duty not yet seen clearly enough to take a particular shape) (Lev. 2). All work involves some satisfaction. If it is simply dropped and left to go stale, it can be mouldy or dry drudgery, involved in all kinds of negative bargaining. If it is brought to the table or the altar, its satisfaction is recognized, and the bread is transformed by the spirit of God who gives it life.

The loaves of the Presence place on the table in the holy place and the bread brought to the altar for offering were eaten with joy. In both cases a "memorial," a part that brought the Presence of God to active memory, was not eaten, but burnt, sent up to God, to symbolize the Divine actually present. For the bread of the Presence, this memorial was the frankincense; for the bread of the offering, it was "a handful of fine flour and oil" and "all of its frankincense," the "handful" meaning that the person making the offering was to take hold, or love, with all his or her strength or soul. The rest was for Aaron and his sons, to be eaten "in a holy place, since it is ... a holy of holies of the offerings by fire to the LORD." This part which the priest in us eats, means the sense we have of working as of ourselves as we carry our goals into life, knowing that the power to work is from God and is God's power with us.

This combination of my taking hold with all my strength, giving my effort to my work, and at the same time trusting the accomplishment and the outcome of each action to the Lord, because the Lord's strength is present, is the offering of my bread. When I bring to the Lord my thought for daily use which I hope to live in my work, penetrated with the oil of God's mercy to me and to my neighbor, and I catch the scent of the joy of God's gifts, a quickening fire kindles and unites with them all, and brings new life. This is the Lord's life brought to life in the work of persons in this world.

The priest was to eat this bread in a holy place since it was a holy of holies of offerings. When Jesus himself drew near and went with the two disciples on their way to Emmaus, they did not recognize him, for the crucifixion had put an end to their hope that "he was the one to redeem Israel." But "when he was at table with them, he took the bread and blessed, and broke it, and gave it to them." And as the bread was broken to be eaten, in the simplest human act, most open to the Lord, it became again the bread of life and Presence, and they knew that it was he.

Turn your mind back to one typical working day, the effort you put in, the work accomplished, the times of joy or satisfaction. Be open to your feelings. What kind of satisfaction did you have? Do you feel tense or peaceful as you think of it? Did only one part of you find satisfaction or was the whole of you content? Where did you find the satisfaction? In achievement? In the simple things of life like having enough to eat or seeing a sunset or seeing someone smile? What are you aware of in yourself as you think of bringing your daily work and life to God?

Read again Leviticus 2:1-3 and 13, and be open to the images in it.

When any one brings a cereal offering as an offering to the LORD, his offering shall be of fine flour; he shall pour oil upon it, and put frankincense on it, and bring it to Aaron's sons the priests. And he shall take from it a handful of the fine flour and oil, with all of its frankincense; and the priest shall burn this as its memorial portion upon the altar, an offering by fire, a pleasing odor to the LORD. And what is left of the cereal offering shall be for Aaron and his sons; it is a most holy part of the offerings by fire to the LORD. . . . You shall season all your cereal offerings with salt; you shall not let the salt of the covenant with your God be lacking from your cereal offering; with all your offerings you shall offer salt.

What element speaks to you? The fine flour of balanced thought and feeling? The oil of mercy? The incense of God's goodness in all things? The salt that makes satisfaction good and part of ordinary life? The very fact of bringing your satisfaction to the altar and not letting it go stale?

Now think back to your own working day, and ask the Lord to help you bring it as an offering, and receive a holy, peaceful satisfaction as the Lord gives you the blessing of wholeness and new life.

Lord, thank you that you are with me in the simplest, daily parts of life. For my life is full of so many little things, and if I could not find you there, I would be lost and lack direction in so much. Thank you that the simplest act of giving and receiving food is most open to your Presence.

Lord, help me with my priorities. Help me to take hold with my full effort, and then trust all results to you. And thank you that I can bring my work to you and know the taste and scent of peaceful satisfaction. Thank you, Lord. Amen.

| Previous: 4. The Altar of Sacrifice | Up: THE HOLY CENTER | Next: 6. Mornings and Evenings |